Adaptive Compute - Survey of Existing Techniques

Note: This is a collection of research notes I put together while exploring adaptive compute techniques in neural networks. Unlike conditional computation approaches like Mixture of Experts (MoE) where compute per token is fixed, these techniques dynamically adjust the amount of computation based on input complexity and task requirements. These notes represent ideas and observations from the research literature as of early 2024.

Introduction

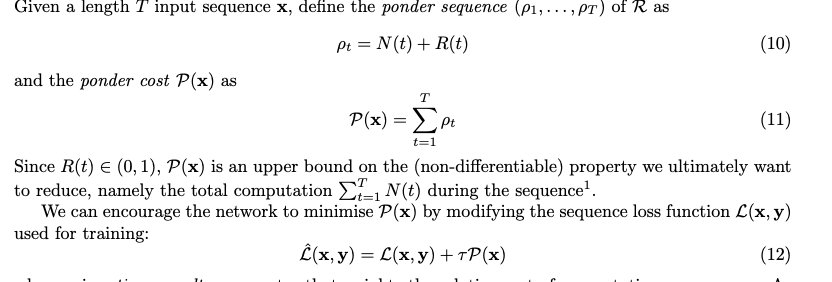

Most machine learning algorithms do not adjust their computational budget based on the complexity of the task they are learning to solve. This adaptation, known as pondering, has been a key research direction in making neural networks more efficient and adaptive. This survey covers various techniques that enable neural networks to dynamically control computation, from early recurrent network approaches to modern transformer architectures.

The key distinction from Mixture of Experts (MoE) models is that while MoE uses conditional computation, the compute per token remains fixed (e.g., routing to 2 out of 8 experts always uses the same FLOPs). True adaptive compute techniques vary the amount of computation based on input complexity.

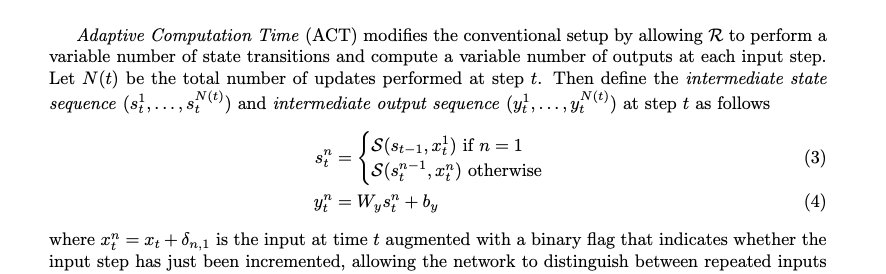

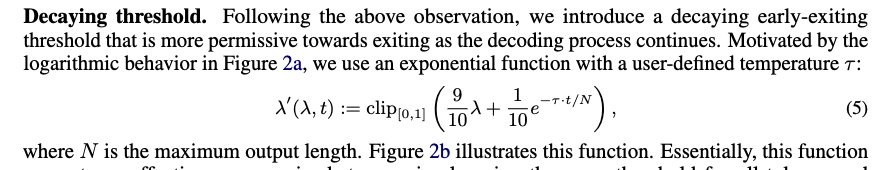

Adaptive Computation Time for Recurrent Neural Networks

Figure 1: Adaptive Computation Time (ACT) mechanism for RNNs

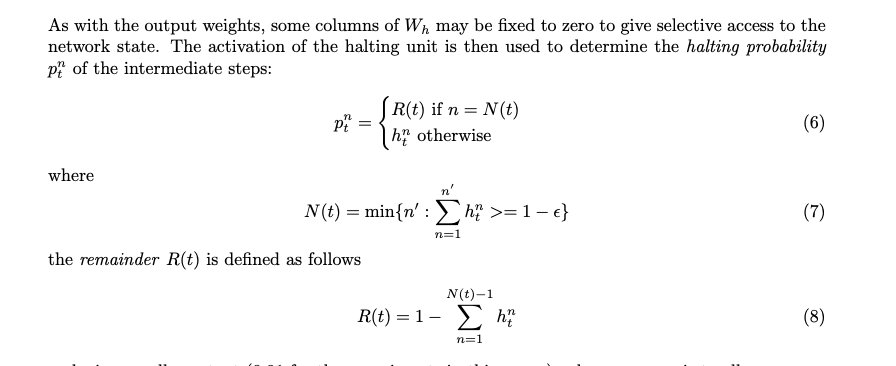

The approach pursued in ACT is to augment the network output with a sigmoidal halting unit whose activation determines the probability that computation should continue. The resulting halting distribution is used to define a mean-field vector for both the network output and the internal network state propagated along the sequence.

A stochastic alternative would be to halt or continue according to binary samples drawn from the halting distribution. However, the mean-field approach has the advantage of using a smooth function of the outputs and states, with no need for stochastic gradient estimates.

Figure 2: ACT halting probability and computation steps

The objective is to minimize the number of computation steps

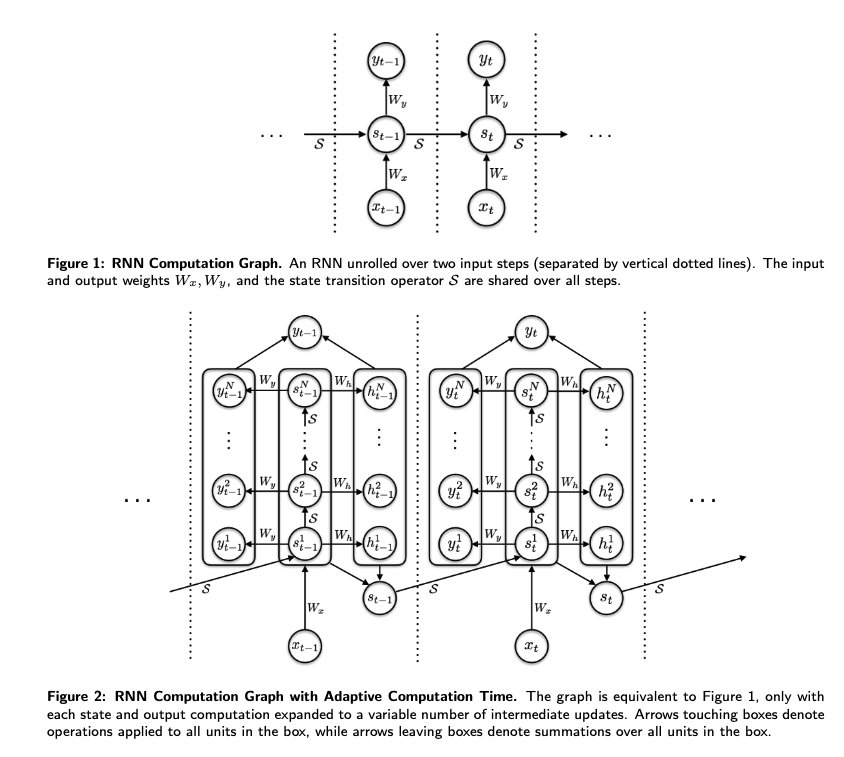

Universal Transformers

Figure 3: Universal Transformer architecture with recurrent refinement

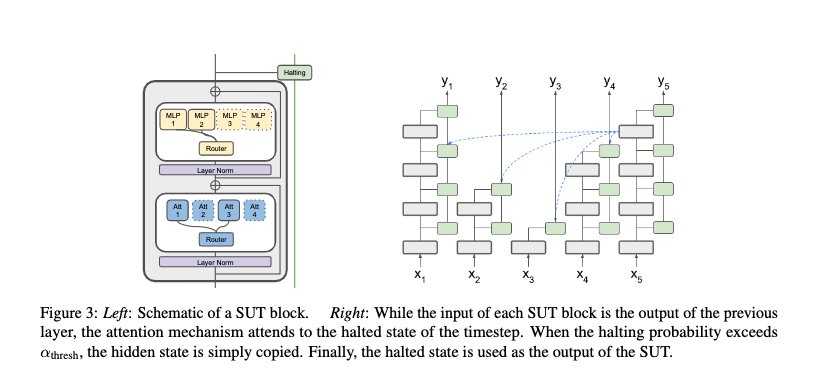

Universal Transformers extend ACT to transformer architectures, which has been shown to improve compositional generalization. The concept of "universality" in computational models refers to the ability of a model to compute any function that can be computed by any other computational device, typically in reference to Turing machines.

Figure 4: Iterative refinement process in Universal Transformers

In each recurrent step, the Universal Transformer iteratively refines its representations for all symbols in the sequence in parallel using a self-attention mechanism, followed by a transformation (shared across all positions and time-steps) consisting of a depth-wise separable convolution or a position-wise fully-connected layer.

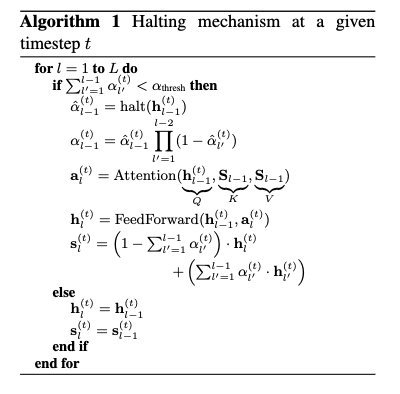

Dynamic Halting Mechanism

The model includes a dynamic per-position halting mechanism, allowing it to choose the required number of refinement steps for each symbol dynamically. This has been shown to improve accuracy on several smaller, structured algorithmic and linguistic inference tasks.

Figure 5: Per-position halting in Universal Transformers

The multi-head attention (MHA) output for one encoder/decoder block is considered state. When you have N blocks of the encoder/decoder in a standard transformer, you have N steps. In Universal Transformers, this N becomes a proxy for timestep in RNNs, and the same ACT model is enforced to decide the halting probability.

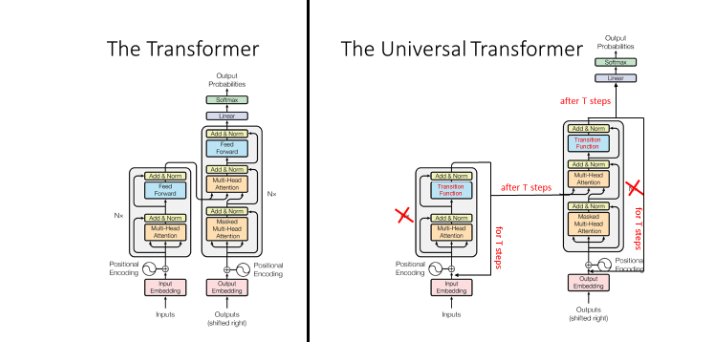

Weight Tying and Computational Trade-offs

Figure 6: Weight tying implications for Universal Transformers

Sharing the parameters among L layers of an L-layer Transformer—while keeping the same model dimensionalities—results in a model with L times fewer parameters (ignoring the input/output layers). Upscaling the size of the layer to compensate for the loss of parameters (essentially by making it L times wider) usually yields a very big layer whose computational requirements in terms of compute and memory are prohibitive in practice.

Despite their potential, Universal Transformers are much less compute-efficient than standard Transformers, and thus they are not popular for parameter-dominated tasks such as modern language modeling.

Depth-Adaptive Transformers

Figure 7: Depth-adaptive transformer with variable layer usage

Unlike dynamic computation in Universal Transformers, which applies the same set of layers iteratively, depth-adaptive transformers apply different layers at every step to adjust both the amount of computation as well as the model capacity.

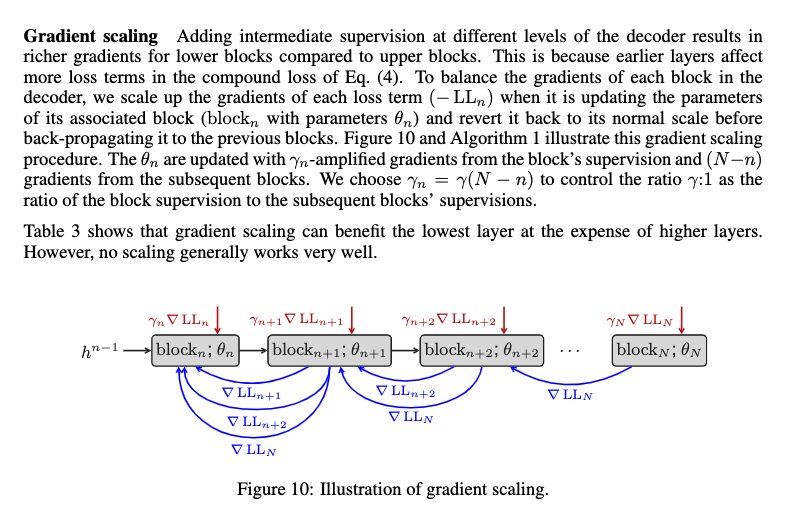

We investigate different mechanisms to control the amount of computation in the decoder network, either for the entire sequence or on a per-token basis. This extends the concept of anytime prediction from computer vision models to structured prediction tasks.

Figure 8: Gradient scaling mechanism for training depth-adaptive models

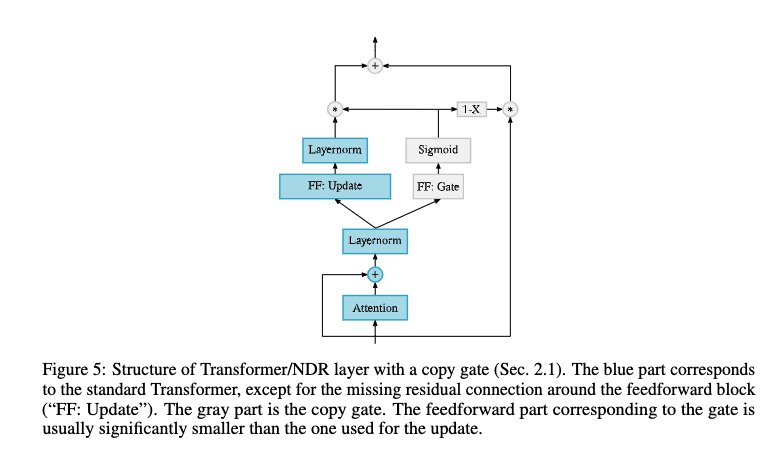

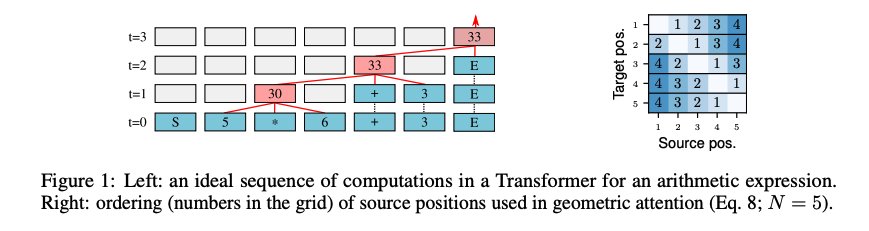

The Neural Data Router

Figure 9: Neural Data Router for adaptive control flow in Transformers

Given an input sequence of length N and a Transformer encoder of depth T, solving an algorithmic task is often about routing the relevant information to the right node/operation at the right time in the T-by-N grid represented by Transformer columns. The task is to learn to draw an adaptive control flow on the canvas of Transformer columns.

Figure 10: Example of adaptive control flow for expression evaluation

In processing an expression like (3 + (2 * 4)) - 5, there are steps where certain operations are critical and others where less substantial transformation might be necessary. In situations where subsequent layers might not add substantial new insights or transformations necessary for the output, skipping these layers could save computational resources without losing essential information or processing quality. Standard Transformers do not allow this.

Parameterized Gating

Crucially, the gate is parameterized as a function of the output of the self-attention, such that the decision to copy or transform the input for each column depends on the states of all columns. This is a crucial difference compared to previously proposed gatings in Transformers, which are solely motivated by training stability.

Mixture of Depths and MoE-Based Approaches

Figure 11: Mixture of depths routing mechanism

Mixture of depths routing is similar to the Neural Data Router concept, allowing different tokens to use different computational depths.

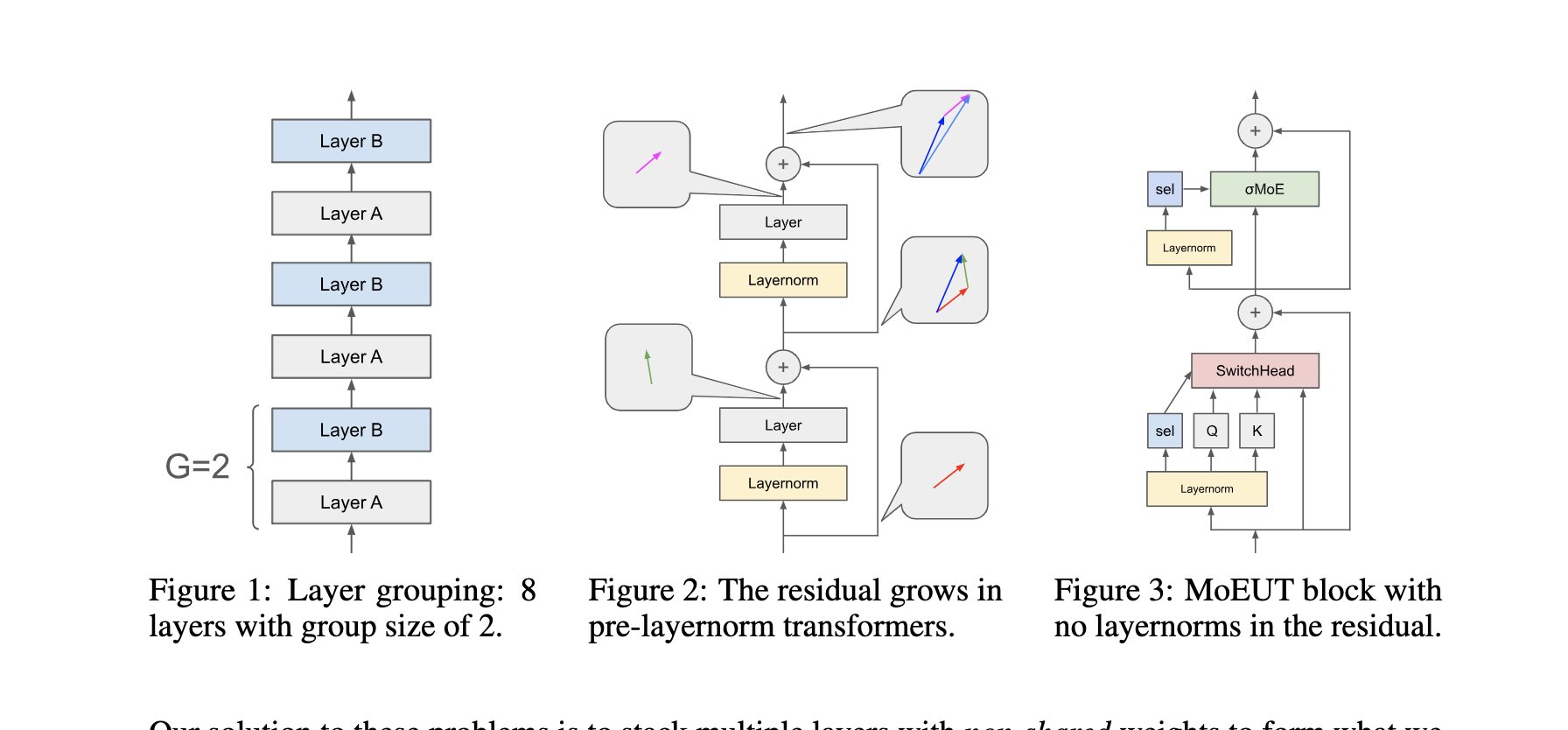

MoEUT: Mixture-of-Experts Universal Transformers

Figure 12: MoEUT architecture combining MoE with Universal Transformers

This is somewhat of a misnomer (although they mentioned the disclaimer) as unlike the Universal Transformers, they do not allow dynamic path selection per token, but are just grouping layers. The name "Universal" here is slightly overloaded.

Sparse Universal Transformers

Figure 13: Sparse computation patterns in Universal Transformers

Sparse Universal Transformers combine the benefits of sparse computation with the iterative refinement of Universal Transformers.

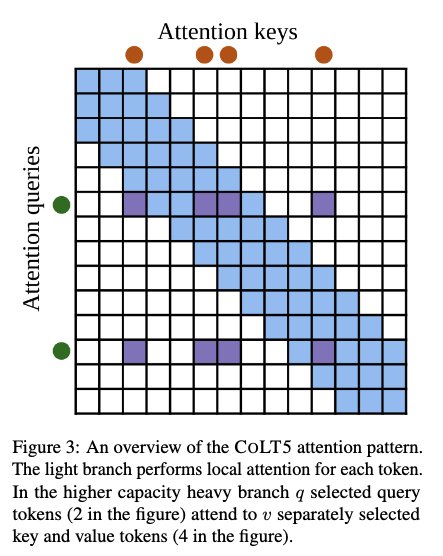

ColT5: Conditional Computation in T5

Figure 14: ColT5 conditional computation mechanism

The ColT5 conditional computation mechanism consists of three components:

- Routing modules - Select important tokens from input

- Conditional feedforward layers - Apply additional computation to routed tokens

- Conditional attention layers - Heavyweight attention for selected tokens

Figure 15: Token routing and selective computation in ColT5

All tokens are processed by standard, lightweight attention and feedforward layers. Routing modules additionally select important tokens from an input at each attention or feedforward layer, and a heavy conditional layer applies additional computation to routed tokens.

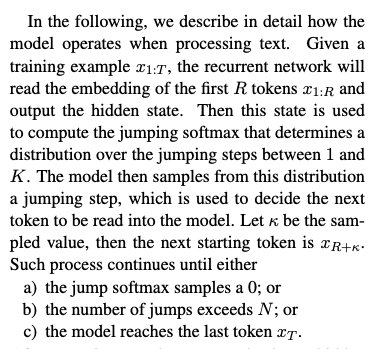

PonderNet: Learning to Ponder

Figure 16: PonderNet probabilistic halting mechanism

Most machine learning algorithms do not adjust their computational budget based on the complexity of the task they are learning to solve. PonderNet addresses this by learning to scale the required computation time via a probabilistic halting policy.

Advantages over ACT

Figure 17: Comparison of PonderNet and ACT halting mechanisms

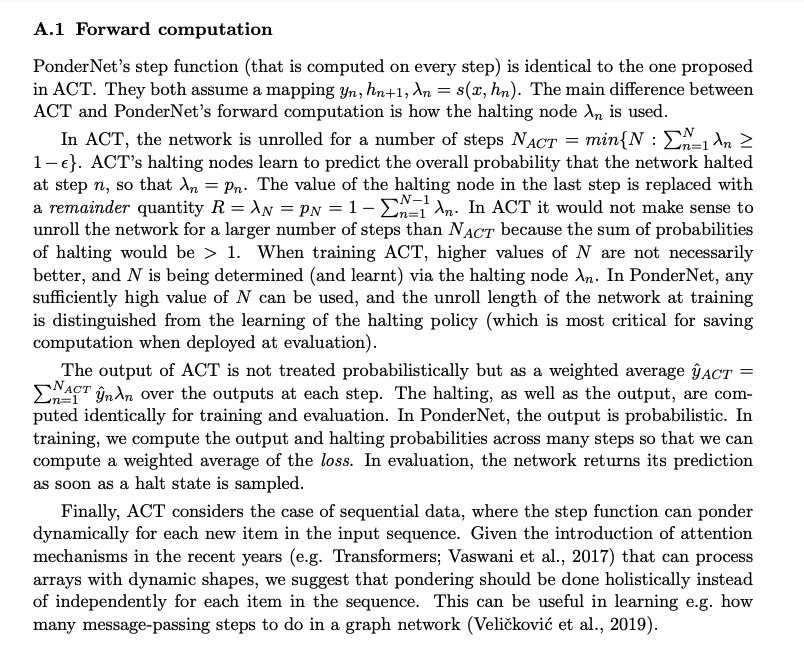

PonderNet improves over Adaptive Computation Time (ACT) in several ways:

- Fully differentiable - Allows for low-variance gradient estimates (unlike REINFORCE)

- Unbiased gradient estimates - Unlike ACT, achieves this by reformulating the halting policy as a probabilistic model

- Less sensitive to hyperparameters - More stable training than ACT

Key Differences: ACT vs PonderNet

Adaptive Computation Time (ACT):

- The network learns when to stop processing based on the cumulative sum of halting probabilities

- The network stops when the sum of

PonderNet:

- Allows for a predetermined, fixed number of steps

- Treats the halting condition probabilistically

- The network can potentially continue processing beyond individual halting signals until the overall condition is met or maximum steps

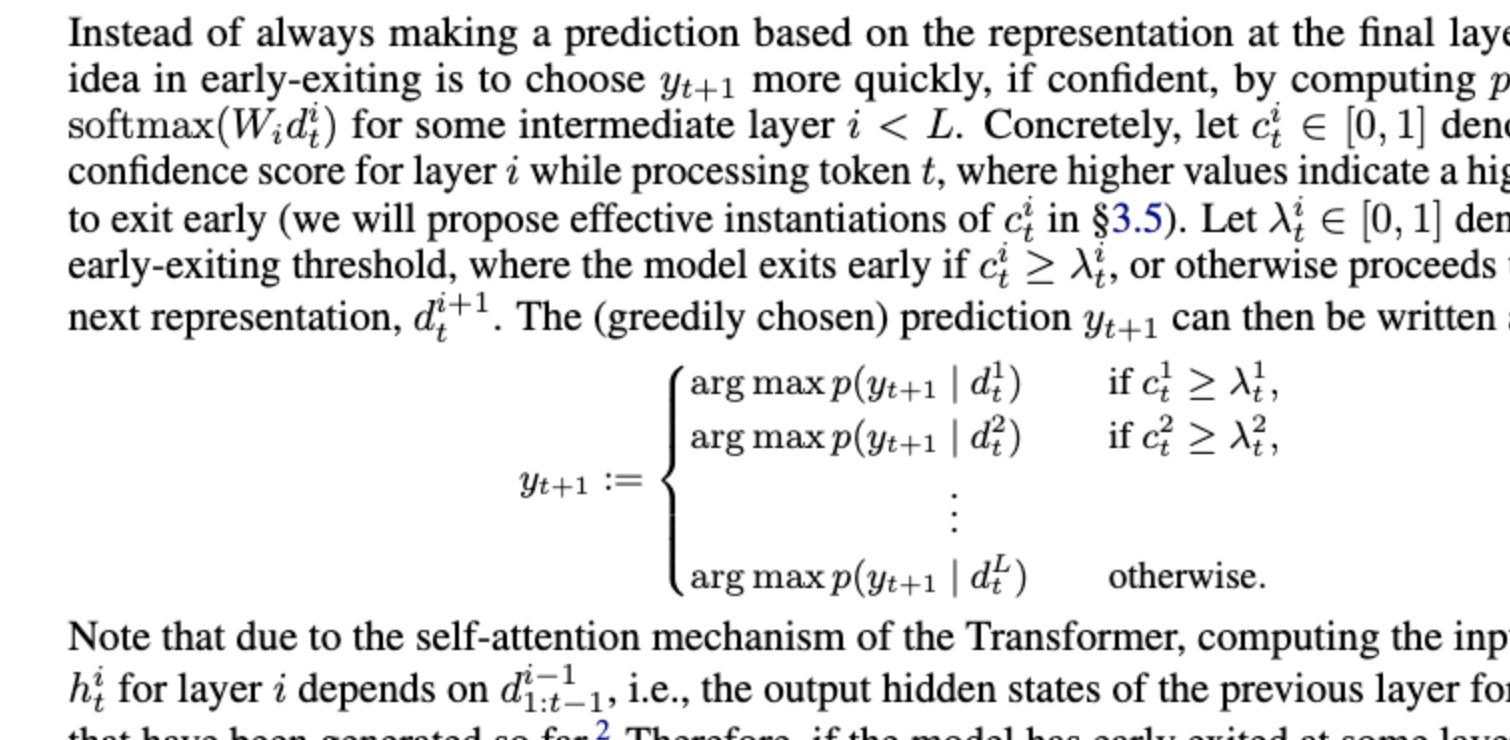

CALM: Confident Adaptive Language Modeling

Figure 18: CALM early exit mechanism based on confidence

CALM (Confident Adaptive Language Modeling) demonstrates the potential of reducing the average complexity of the model and accelerating inference by approximately 3× while reliably controlling for high performance.

Figure 19: CALM inference speedup and accuracy trade-offs

The Learn then Test framework of multiple hypothesis testing is used to guarantee performance bounds while enabling early exits based on model confidence.

State Copying in Early Exit Methods

Figure 20: State copying mechanism in depth-adaptive models

The main takeaway from depth-adaptive early exit methods is the need for state copying to maintain information flow when layers are skipped.

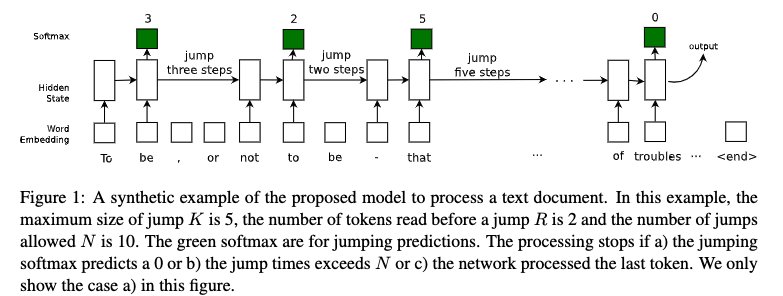

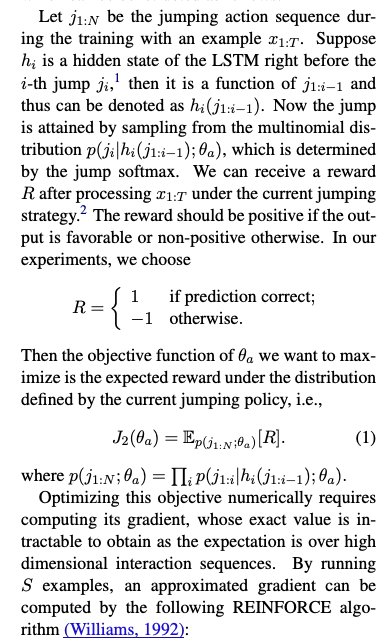

Learning to Skim Text

Figure 21: Learning to skim text for efficient reading

This approach enables models to learn which parts of the input text require detailed processing and which can be skimmed over quickly.

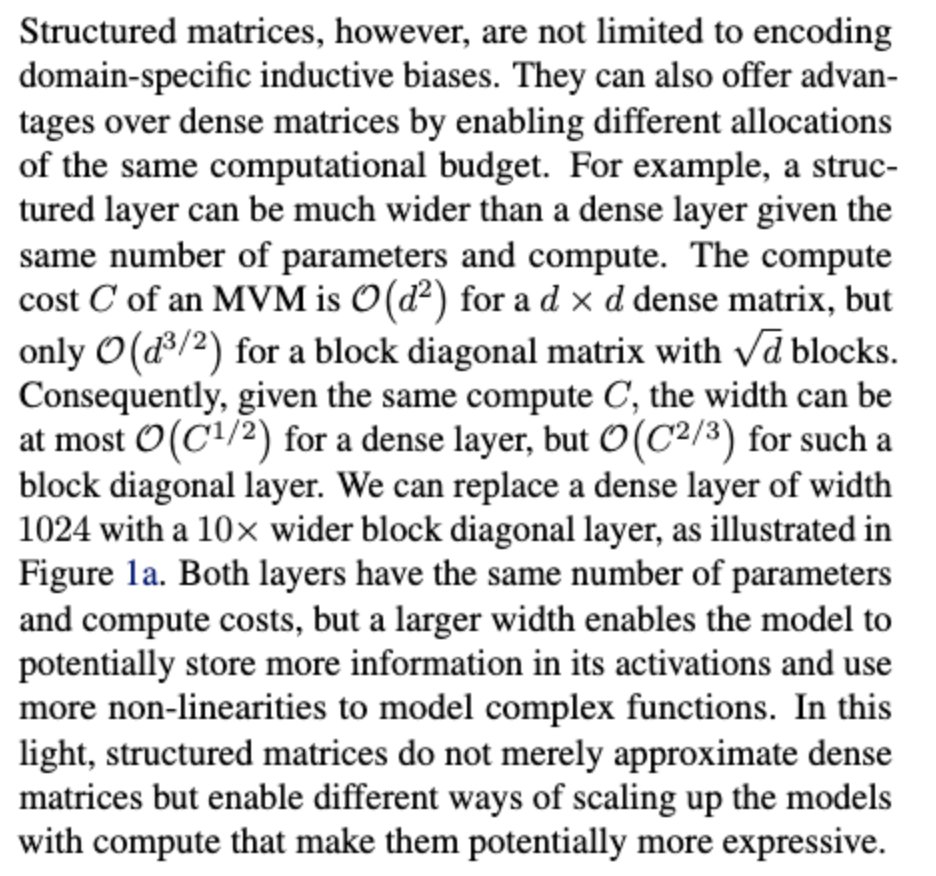

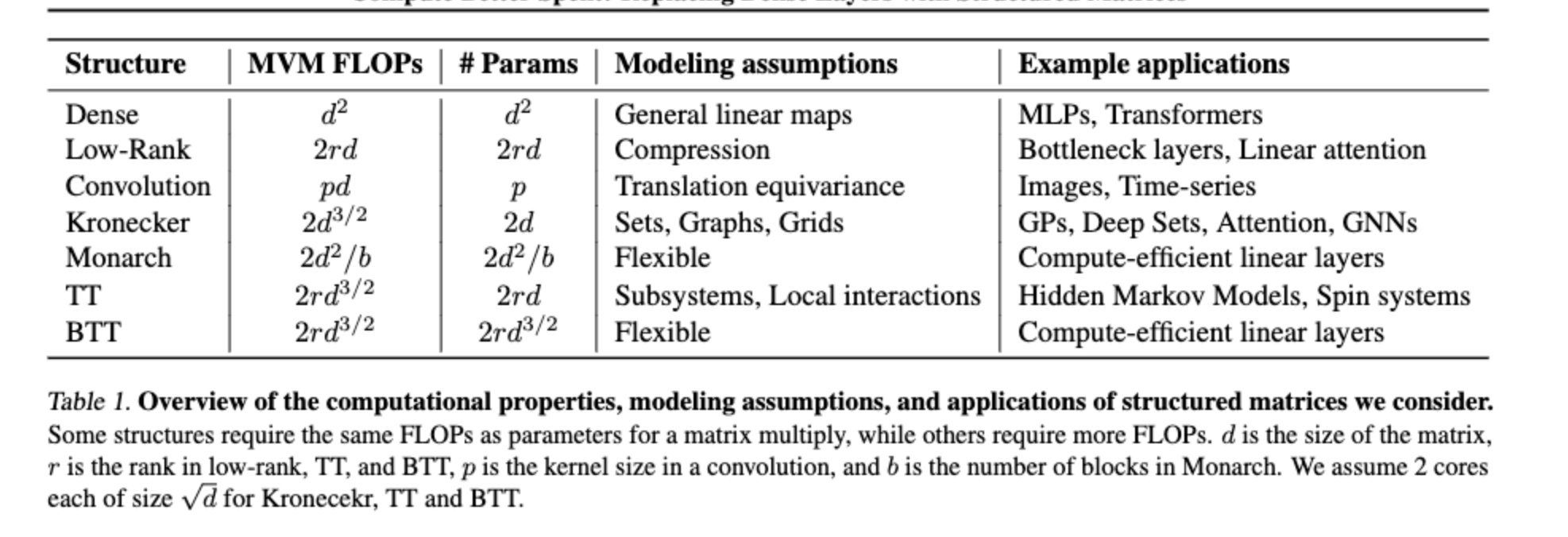

Structured Matrices and Efficient Computation

Figure 22: Tensor train decomposition for efficient dense layers

Compute Better Spent: Replacing Dense Layers with Structured Matrices

Tensor train decomposition provides a way to replace expensive dense matrix operations with more efficient structured computations, reducing both memory and computational requirements.

Sample-Based Adaptive Computation

Determining Which Samples Need More Compute

Figure 23: Analyzing which samples require more computation

Not all inputs require the same amount of computation. Learning to identify which samples need more processing is key to efficient adaptive computation.

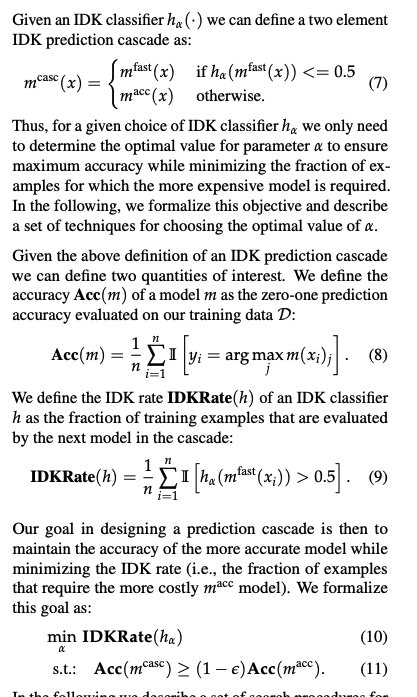

IDK Cascades: Fast Deep Learning by Learning Not to Overthink

Figure 24: IDK Cascades - early exit when model is confident

IDK Cascades enable fast deep learning by learning when the model doesn't need to "overthink" a problem, allowing for early exits when confidence is high.

Rigging the Lottery: Making All Tickets Winners

This work explores how to make all subnetworks within a larger network effective, building on the lottery ticket hypothesis.

SHARCS: Efficient Transformers through Routing with Dynamic Width Sub-networks

Figure 25: SHARCS routing with dynamic width sub-networks

SHARCS achieves efficiency through routing tokens to dynamically-sized sub-networks, adapting both depth and width based on input requirements.

Query Routing and Hybrid Approaches

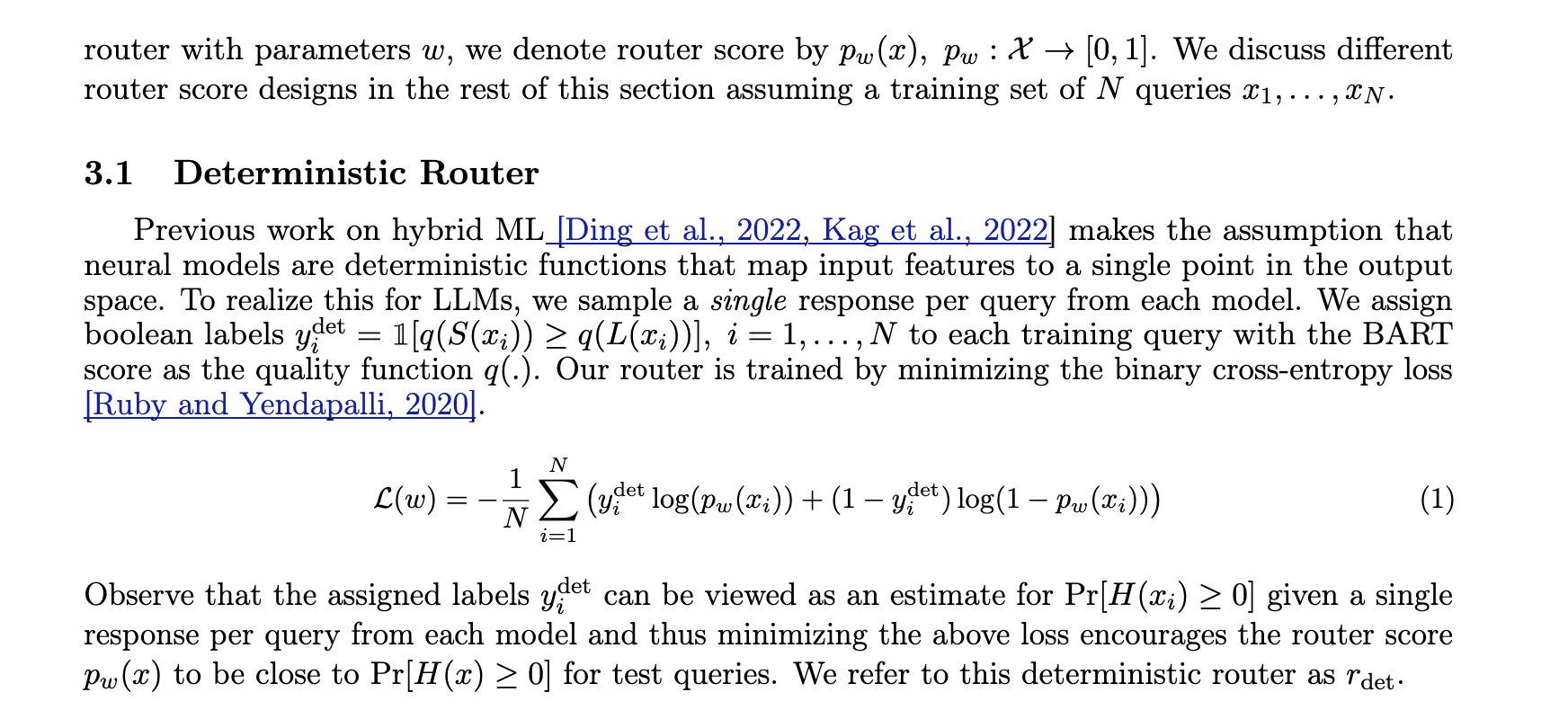

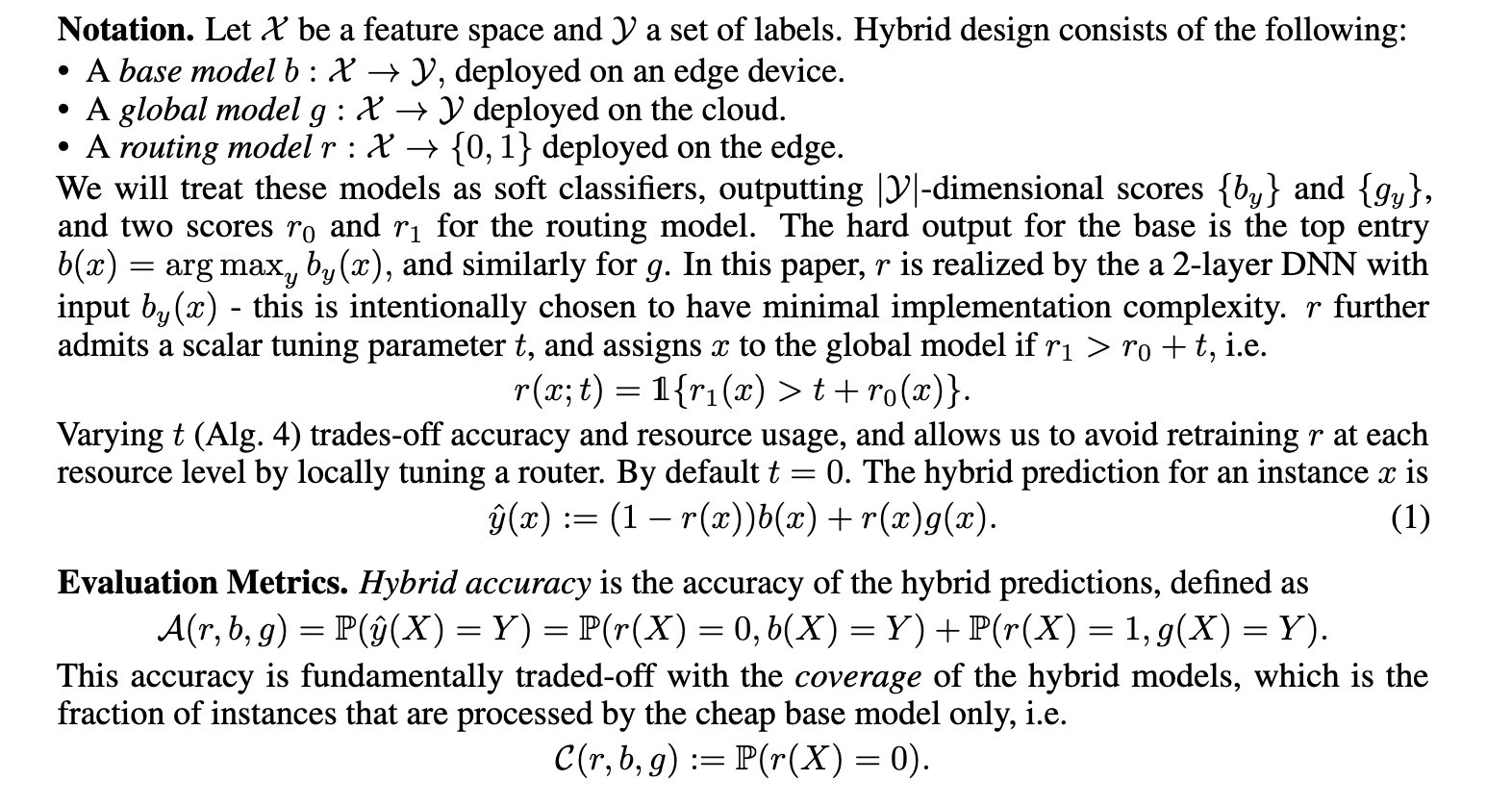

Hybrid LLM: Cost-Efficient and Quality-Aware Query Routing

Figure 26: Hybrid LLM query routing between models of different sizes

Hybrid LLM approaches route queries to different model sizes based on complexity, using small models for simple queries and larger models only when necessary. This enables cost-efficient inference while maintaining high quality.

Efficient Edge Inference by Selective Query

Selective querying enables efficient inference at the edge by deciding which computations are necessary and which can be skipped or delegated.

Key Insights and Takeaways

Dynamic Halting: Both ACT and PonderNet demonstrate that learning when to stop computation can significantly improve efficiency, with PonderNet offering more stable training through probabilistic formulation.

Per-Token Adaptation: Universal Transformers and Neural Data Router show that different tokens may require different amounts of computation, enabling fine-grained adaptive computation.

Early Exit Mechanisms: CALM and depth-adaptive transformers demonstrate that not all inputs need full model depth, with confidence-based early exits providing 2-3× speedups.

Routing vs. Halting: Techniques like ColT5 and SHARCS show that routing important tokens to heavier computation while processing others lightly can be more efficient than halting.

Trade-offs: Universal Transformers with weight tying show that while parameter efficiency improves, computational efficiency may suffer, highlighting the importance of considering multiple efficiency dimensions.

Structured Computation: Tensor train decomposition and structured matrices offer orthogonal approaches to reducing compute through mathematical structure rather than conditional computation.

Sample-Level Adaptation: IDK Cascades and Hybrid LLM demonstrate that routing at the sample/query level (choosing which model to use) can be as important as token-level adaptation.

References and Further Reading

- Universal Transformers: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1807.03819

- Conditional computation: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1511.06297

- Neural Turing machines: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1410.5401

- Connectionist Temporal Classification: https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~graves/icml_2006.pdf

- BrancyNet: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1709.01686

- Not all Attention is needed: https://www.arxiv.org/pdf/1912.00349

- Dynamic routing between capsules: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1710.09829

- Blockdrop: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1711.08393

- Dynamic Control Flow MoE: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1805.01772

- BERT early exit: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2020/file/d4dd111a4fd973394238aca5c05bebe3-Paper.pdf

- FastBERT: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2004.02178

- Scalable Adaptive computation: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2212.11972

- Lottery Ticket Hypothesis: https://www.arxiv.org/pdf/1911.11134

- Learning to Skip for Language Modeling: https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.15436

- ColT5: https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.09752

- Hybrid LLM: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2404.14618

- Efficient Edge Inference: https://par.nsf.gov/servlets/purl/10447699

- Tensor Train Decomposition: https://bayesgroup.github.io/team/arodomanov/tt_hse16_slides.pdf

Conclusion

Adaptive compute techniques represent a promising direction for making neural networks more efficient and capable. Unlike fixed-compute approaches like standard MoE, these methods truly adapt the amount of computation to the input complexity. While challenges remain in training stability and implementation complexity, the potential for significant efficiency gains—often 2-3× or more—makes this an important area of ongoing research.

The field has evolved from simple halting mechanisms in RNNs (ACT) to sophisticated routing and early-exit strategies in modern transformers (CALM, ColT5, SHARCS). Future work will likely focus on combining these techniques, improving training stability, and extending them to ever-larger models where efficiency gains become increasingly critical.